I normally write abstractly about work I’ve done for other people (for obvious reasons), but I’ve been given permission to write about a website, Vocal, that I did some SRE work on last year. I actually gave a presentation at GraphQL Sydney back in February, but this blog post got delayed a bit.

Vocal is a GraphQL-based website that got traction and hit scaling problems that I got called in to fix. Here’s what I did. Obviously, you’ll find this post useful if you’re scaling another GraphQL website, but most of it’s representative of what you have to deal with when a site first gets enough traffic to cause technical problems. If website scalability is a key interest of yours, you might want to read my recent post about scalability first.

Vocal

Vocal is a blogging platform publishing everything from diaries to movie reviews to opinion pieces to recipes to professional and amateur photography to beauty and lifestyle tips and poetry and (of course) cute dog and cat pictures.

One thing that’s a bit different about Vocal is that it lets people get paid for producing works that viewers find interesting. Authors get a small amount of money per page view, and can also receive donations from other users. There are many professionals using the platform to show off their work, but most users are everyday people using Vocal as a fun hobby that happens to make some extra pocket money as a bonus.

Vocal is the product of Jerrick Media, a New Jersey startup. Update: Jerrick Media has rebranded to

Creatd and is now listed on the NASDAQ. Development started in 2015 in

collaboration with Thinkmill, a medium-sized Sydney software development

consultancy that specialises in JavaScript, React and GraphQL.

Some spoilers for the rest of this post

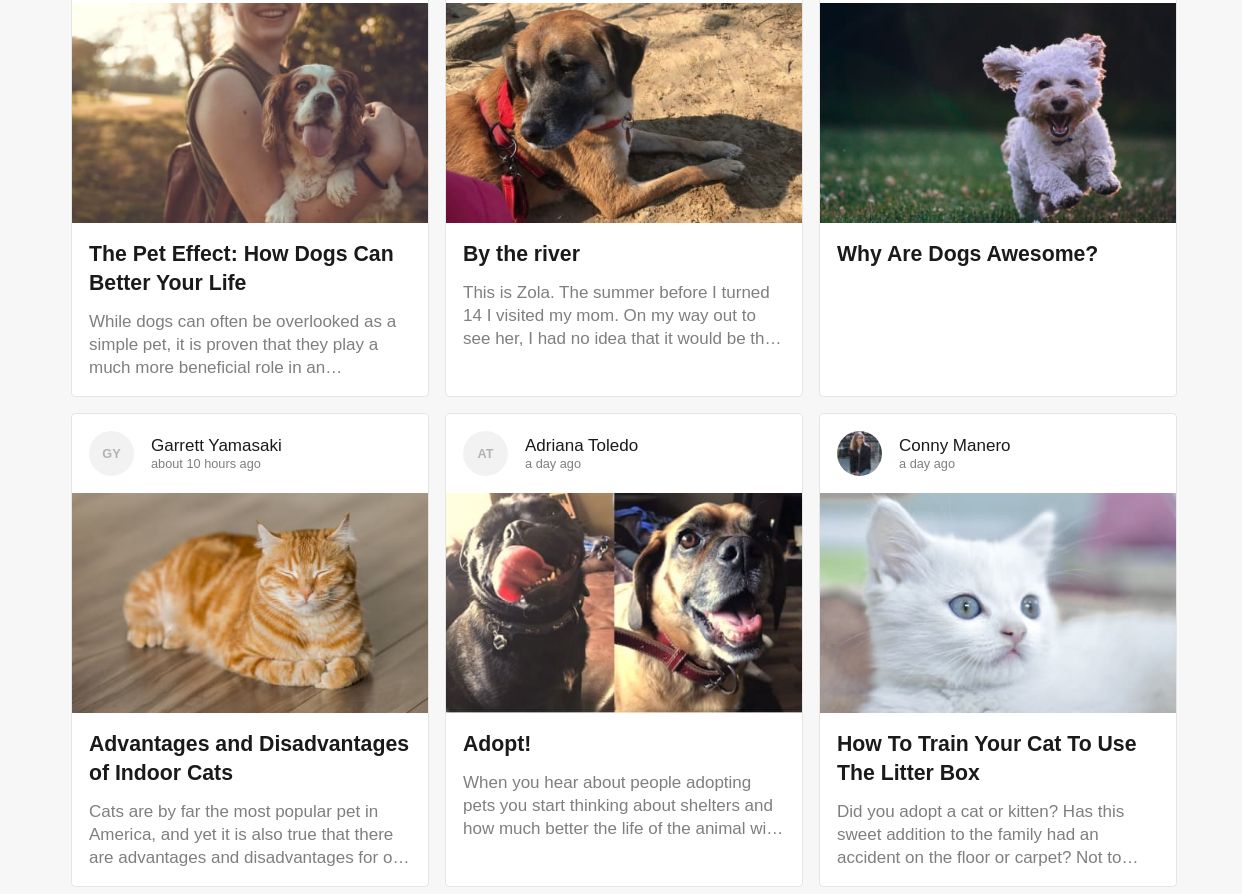

I was told that unfortunately I can’t give hard traffic numbers for legal reasons, but publicly available information can give an idea. Alexa ranks all websites it knows of by traffic level. Here’s a plot of Alexa rank I showed in my talk, showing growth from November 2019 up to getting ranked number 5,567 in the world by February.

It’s normal for the curve to slow down because it requires more and more traffic to win each position. Vocal is now at around #4,900. Obviously there’s a long way to go, but that’s not shabby at all for a startup. Most startups would gladly swap their Alexa rank with Vocal.

Shortly after the site was upgraded, Creatd ran a marketing campaign that doubled traffic. All we had to do on the technical side was watch numbers go up in the dashboards. In the past 9 months since launch, there have only been two platform issues needing staff intervention: the once-in-five-years AWS RDS certificate rotation that landed in March, and an app rollout hitting a Terraform bug. As an SRE, I’ve been very happy with how little platform busywork Vocal needs to keep running. Update: The system also handled the 2020 US election without drama, too.

Here’s an overview of the technical stuff I’ll talk about in this post:

- Technical and historical background

- Database migration from MongoDB to Postgres

- Deployment infrastructure revamp

- Making the app compatible with scaling

- Making HTTP caching work

- Miscellaneous performances tweaks

Some background

Thinkmill built a website using Next.js (a React-based web framework), talking to a GraphQL API provided by Keystone in front of MongoDB. Keystone is a GraphQL-based headless CMS library: you define a schema in JavaScript, hook it up to some data storage, and get an automatically generated GraphQL API for data access. It’s a free and open-source software project that’s commercially backed by Thinkmill.

Vocal V2

The version 1 of Vocal got traction. It found a userbase that liked the product, and it grew, and eventually Creatd asked Thinkmill to help develop a version 2, which was successfully launched in September last year. The Creatd staff avoided the second system effect by generally basing changes on user feedback, so they were mostly UI and feature changes that I won’t go into. Instead, I’ll talk about the stuff I was brought in for: making the new site more robust and scalable.

For the record, I’m thankful that I got to work with Creatd and Thinkmill on Vocal, and that they let me present this story, but I’m still an independent consultant. I wasn’t paid or even asked to write this post, and this is still my own personal blog.

The database migration

Thinkmill suffered several scalability problems with using MongoDB for Vocal, and decided to upgrade Keystone to version 5 to take advantage of its new Postgres support.

If you’ve been in tech long enough to remember the “NoSQL” marketing from the end of the 00s, that might sound funny. A major theme of NoSQL marketing was that relational (SQL) databases like Postgres aren’t as scalable as “webscale” NoSQL databases like MongoDB. Technically that’s true, but the scalability of NoSQL databases comes from compromises in the variety of queries that can be efficiently handled. There are places for simple, non-relational databases (like document and key-value databases). However, when they’re used as general-purpose backends for apps, the apps often outgrow the querying limitations of the database before they outgrow the theoretical scaling limit of a relational database. Most of Vocal’s DB original queries worked just fine with MongoDB, but over time more and more queries needed hacks to work at all.

In terms of technical requirements, Vocal is very similar to Wikipedia, one of the biggest sites in the world. Wikipedia runs on MySQL (or rather, its fork, MariaDB). Sure, some significant engineering is needed to make that work, but relational databases aren’t a serious threat to Vocal’s scaling in the foreseeable future.

I did a comparison at one time, and the managed AWS RDS Postgres instances cost less than a fifth of the old MongoDB instances, yet CPU usage of the Postgres instances was still under 10%, despite serving more traffic than the old site. That’s mostly because of a few important queries that just never were efficient under the document database architecture.

The migration could be a blog post of its own, but basically a Thinkmill dev built an ETL pipeline using MoSQL to do the heavy lifting. Keystone support for Postgres was still new, but it’s a FOSS project so I was able to fix the problems we had with its SQL generation performance. For that kind of stuff, I always recommend Markus Winand’s SQL blogs: Use the Index Luke and Modern SQL. His writing is friendly and accessible even to people who have more important things than SQL to worry about, yet it has most of the theory you need most of the time. A good, DB-specific book on performance gives you the rest if you still have problems.

The platform

The architecture

V1 was a couple of Node.js apps running on a single virtual private server (VPS) behind Cloudflare as a CDN. I’m a fan of avoiding overengineering as a high priority, so that gets a thumbs up from me. However, by the time V2 development started, it was obvious that Vocal had outgrown that simple architecture. It didn’t give Thinkmillers many options when handling big traffic spikes, and it made updates hard to deploy safely and without downtime.

Here’s the new architecture for V2:

Basically, the two Node.js apps have been replicated and put behind a load balancer. Yes, that’s it. Some people expect scalable architecture to be more complicated than that, but I’ve worked on sites that are orders of magnitude bigger than Vocal but are still just replicated services behind load balancers, with DB backends. If you think about it, if the platform architecture needs to keep getting more complicated to serve more traffic, it’s not really “scalable”. Website scalability is mostly about fixing the many little implementation details that prevent scaling.

Vocal’s architecture might need a few additions if traffic grows enough, but the main reason it would get more complicated is new features. For example, if (for some reason) Vocal needed to handle real-time geospatial data in future, that would be a very different technical beast from blog posts, so I’d expect architectural changes for it. Most of the complexity in big site architecture is because of feature complexity.

It’s normal to not know what the future architecture needs to look like, so I always recommend starting as simple as you can. Fixing an architecture that’s too simple is easier and cheaper than fixing an architecture that’s too complex. Also, an unnecessarily complex architecture is more likely to have mistakes, and those mistakes will be harder to debug.

By the way, Vocal happened to be split into two apps, but that’s not important. A common scaling mistake is to prematurely split an app into smaller services in the name of scalability, but split the app in the wrong place and cause more scalability problems overall. Vocal could have scaled okay as a monolithic app, but the split is also in a good place.

The infrastructure

Thinkmill has a few people who have experience working with AWS, but it’s primarily a dev shop and needed something more hands off than the old Vocal deployment. I ended up deploying the new Vocal on AWS Fargate, which is a relatively new backend to Elastic Container Service (ECS). In the old days, many people wanted ECS to be a simple “run my Docker container as a managed service” product, and were disappointed that they still had to build and manage their own server cluster. With ECS Fargate, AWS manages the cluster. It supports running Docker containers with the basic nice things like replication, health checking, rolling updates, autoscaling and simple alerting.

A good alternative would have been a managed Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) like App Engine or Heroku. Thinkmill was already using them for simple projects, but often needed more flexibility with other projects. There are much bigger sites running on PaaSes, but Vocal is at a scale where a custom cloud deployment can make sense economically.

Another obvious alternative would have been Kubernetes. Kubernetes has a lot more features than ECS Fargate, but it’s a lot more expensive — both in resource overhead, and the staffing needed for maintenance (such as regular node upgrades). As a rule, I don’t recommend Kubernetes to any place that doesn’t have dedicated DevOps staff. Fargate has the features Vocal needs, and has let Thinkmill and Creatd focus on website improvements, not infrastructure busywork.

Yet another option was “Serverless” function products like AWS Lambda or Google Cloud Functions. They’re great for handling services with very low or highly irregular traffic, but (as I’ll explain) ECS Fargate’s autoscaling is enough for Vocal’s backend. Another plus of these products is that they allow developers to deploy things in cloud environments without needing to learn a lot about cloud environments. The tradeoff is that the Serverless product becomes tightly coupled to the development process, and to the testing and debugging processes. Thinkmill already had enough AWS expertise in-house to manage a Fargate deployment, and any dev who knows how to make a Node.js Express Hello World app can work on Vocal without learning anything about either Serverless functions or Fargate.

An obvious downside of ECS Fargate is vendor lock-in. However, avoiding vendor lock-in is a tradeoff like avoiding downtime. If you’re worried about migrating, it doesn’t make sense to spend more on platform independence than you would on a migration. The total amount of Fargate-specific code in Vocal is <500 lines of Terraform. The most important thing is that the Vocal app code itself is platform agnostic. It can run on normal developer machines, and then be packaged up into a Docker container that can run practically anywhere a Docker container can, including ECS Fargate.

Another downside of Fargate is that it’s not trivial to set up. Like most things in AWS, it’s in a world of VPCs, subnets, IAM policies, etc. Fortunately, that kind of stuff is quite static (unlike a server cluster that requires maintenance).

Making a scaling-ready app

There’s a bunch of stuff to get right if you want to run an app painlessly at scale. You’re doing well if you follow the Twelve-Factor App design, so no need to repeat that stuff here.

There’s no point building a “scalable” system if staff can’t operate it at scale — that’s like putting a jet engine on a unicycle. An important part of making Vocal scalable was setting up stuff like CI/CD and infrastructure as code. Similarly, some deployment ideas aren’t worth it because they make production too different from the development environment (see also point #10 of the Twelve-Factor App). Every difference between production and development slows app development and (in practice) will lead to a bug eventually.

Caching

Caching is a really big topic — I once gave a talk on just HTTP caching, but that was still relatively basic. I’ll stick to the essentials for GraphQL here.

First, an important warning: Whenever you have performance problems, you might wonder, “Can I make this faster by putting this value into a cache for future reuse?” Microbenchmarks will practically always tell you the answer is “yes”. However, putting caches everywhere will tend to make your overall system slower, thanks to problems like cache coherency. Here’s my mental checklist for caching:

- Ask if the performance problem needs to be solved with caching

- Really ask (non-caching performance wins tend to be more robust)

- Ask if the problem can be solved by improving existing caches

- If all else fails, maybe add a new cache

One cache system you’ll always have in the Web is the HTTP caching system, so a corollary is that it’s a good idea to use HTTP caching effectively before trying to add extra caches. I’ll focus on that in this post.

Another very common trap is using a hash map or something inside the app for caching. It works great in local development but performs badly when scaled. The best thing is to use an explicit caching library that supports pluggable backends like Redis or Memcached.

The basics

There are two types of caches in the HTTP spec: private and public. Private caches are caches that don’t share data with multiple users — in practice, the user’s browser cache. Public caches are all the rest. They include ones under your control (such as CDNs or servers like Varnish or Nginx) and ones that aren’t (proxies). Proxy caches are rarer in today’s HTTPS world, but some corporate networks have them.

Caching lookup keys are normally based on URLs, so caching is less painful if you stick to a “same content, same URL; different content, different URL” rule. I.e., give each page a canonical URL, and avoid “clever” tricks returning varying content from one URL. Obviously, this has implications for GraphQL API endpoints (that I’ll discuss later).

Your own servers can take custom configuration, but the primary way to configure HTTP caching is through HTTP

headers you set on web responses. The most important header is cache-control. The following says that all caches down the line may cache

the page for up to 3600 seconds (one hour):

cache-control: max-age=3600, public

For user-specific pages (such as user settings pages), it’s important to use private instead of public to tell public caches not to store the response and serve it to

other users.

Another common header is vary. This tells caches that the

response varies based on some things other than the URL. (Effectively it adds HTTP headers to the the cache key,

alongside the URL.) It’s a very blunt tool, which is why it’s better to use a good URL structure instead if possible,

but an important use case is telling browsers that the response depends on the login cookie, so that they update pages

on login/logout.

vary: cookie

If a page can vary based on login status, you need cache-control:

private (and vary: cookie) even on the public, logged

out version, to make sure responses don’t get mixed up.

Other useful headers include etag and last-modified, but I won’t cover them here. You might still see some old

headers like expires and pragma: cache. They were made obsolete by HTTP/1.1 back in 1997, so I

only use them if I want to disable caching and I’m feeling paranoid.

Clientside headers

Less well known is that the HTTP spec allows cache-control

headers to be used in client requests to reduce the cache time and get a fresher response. Unfortunately max-age greater than 0 doesn’t seem to be widely supported by browsers,

but no-cache can be useful if you sometimes need a fresh

response after an update.

HTTP caching and GraphQL

As above, the normal cache key is the URL. But GraphQL APIs often use just one endpoint (let’s call it /api/). If you want a GraphQL query to be cachable, you need the query

and its parameters to appear in the URL path, like /api/?query={user{id}}&variables={"x":99} (ignoring URL escaping).

The trick is to configure your GraphQL client to use HTTP GET requests for queries (e.g., set useGETForQueries for apollo-link-http).

Mutations mustn’t be cached, so they still need to use HTTP POST requests. With POST requests, caches will only see

/api/ as the URL path, but caches will refuse to cache POST

requests outright. Remember: GET for non-mutating queries, POST for mutations. There’s a case where you might want to

avoid GET for a query: if the query variables contain sensitive information. URLs have a habit of appearing in log

files, browser history and chat channels, so sensitive information in URLs is usually a bad idea. Things like

authentication should be done as non-cachable mutations, anyway, so this is a rare case, but one worth remembering.

Unfortunately, there’s a problem: GraphQL queries tend to be much larger than REST API URLs. If you simply switch on

GET-based queries, you’ll get some pretty big URLs, easily bigger than the ~2000 byte limit before some popular

browsers and servers just won’t accept them. A solution is to send some kind of query ID, instead of sending the whole

query. (I.e., something like /api/?queryId=42&variables={"x":99}.) Apollo GraphQL server supports

two ways of doing this.

One way is to extract all the GraphQL queries from the code and build a lookup table that’s shared serverside and clientside. One downside is that it makes the build process more complicated. Another downside is that it couples the client project to the server project, which defeats a major selling point of GraphQL. Yet another downside is that version X of your code might recognise a different set of queries from version Y of your code. This is a problem because 1) your replicated app will serve multiple versions during an update rollout, or rollback, and 2) clients might use cached JavaScript, even as you upgrade or downgrade the server.

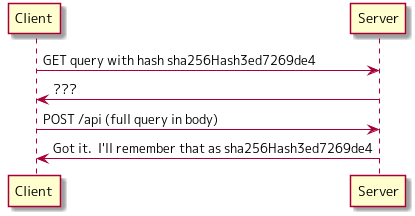

Another way is what Apollo GraphQL calls Automatic Persisted Queries (APQs). With APQs, the query ID is a hash of the query. The client optimistically makes a request to the server, referring to the query by hash. If the server doesn’t recognise the query, the client sends the full query in a POST request. The server stores that query by hash so that it can be recognised in future.

HTTP caching and Keystone 5

As above, Vocal uses Keystone 5 for generating its GraphQL API, and Keystone 5 works with Apollo GraphQL server. How do we actually set the caching headers?

Apollo supports cache hints on GraphQL schemas. The neat thing is that Apollo gathers all the hints for everything that’s touched by a query, and then it automatically calculates the appropriate overall cache header values. For example, take this query:

query userAvatarUrl {

authenticatedUser {

name

avatar_url

}

}If name has a max age of one day, and the avatar_url has a max age of one hour, the overall cache max age would be

the minimum, one hour. authenticatedUser depends on the login

cookie, so it needs a private hint, which overrides the

public on the other fields, so the resulting header would be

cache-control: max-age=3600, private.

I added cache hint support to Keystone lists and fields. Here’s a simple example of adding a cache hint to a field in the to-do list demo from the docs:

const keystone = new Keystone({

name: 'Keystone To-Do List',

adapter: new MongooseAdapter(),

});

keystone.createList('Todo', {

schemaDoc: 'A list of things which need to be done',

fields: {

name: {

type: Text,

schemaDoc: 'This is the thing you need to do',

isRequired: true,

cacheHint: {

scope: 'PUBLIC',

maxAge: 3600,

},

},

},

});One more problem: CORS

Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) rules create a frustrating conflict with caching in an API-based website.

Before getting stuck into the problem details, let me jump to the easiest solution: putting the main site and API onto one domain. If your site and API are served from one domain, you won’t have to worry about CORS rules (but you might want to consider restricting cookies). If your API is specifically for the website, this is the cleanest solution, and you can happily skip this section.

In Vocal V1, the Website (Next.js) and Platform (Keystone GraphQL) apps were on different domains (vocal.media and api.vocal.media). To protect users from malicious websites, modern

browsers don’t just let one website interact with another. So, before allowing vocal.media to make requests to api.vocal.media, the browser would make a “pre-flight” check to

api.vocal.media. This is an HTTP request using the

OPTIONS method that essentially asks if the cross-origin

sharing of resources is okay. After getting the okay from the pre-flight check, the browser makes the normal request

that was originally intended.

The frustrating thing about pre-flight checks is that they are per-URL. The browser makes a new OPTIONS request for each URL, and the server response applies to that

URL. The server can’t say that

vocal.media is a trusted origin for all api.vocal.media requests. This wasn’t a serious problem when

everything was a POST request to the one api endpoint, but after giving every query its own GET-able URL, every query

got delayed by a pre-flight check. For extra frustration, the HTTP spec says OPTIONS requests can’t be cached, so you can find that all your GraphQL

data is beautifully cached in a CDN right next to the user, but browsers still have to make pre-flight requests all the

way to the origin server every time they use it.

There are a few solutions (if you can’t just use a shared domain).

If your API is simple enough, you might be able to exploit the exceptions to the CORS rules.

Some cache servers can be configured to ignore the HTTP spec and cache OPTIONS requests anyway (e.g., Varnish-based caches and AWS CloudFront).

This isn’t as efficient as avoiding the pre-flight requests completely, but it’s better than the default.

Another (really hacky) option is JSONP. Beware: you can create security bugs if you don’t get this right.

Making Vocal more cachable

After making HTTP caching work at the low level, I needed to make the app take better advantage of it.

A limitation of HTTP caching is that it’s all-or-nothing at the response level. Most of a response can be cachable, but if a single byte isn’t, all bets are off. As a blogging platform, most Vocal data is highly cachable, but in the old site almost no pages were cachable at all because of a menu bar in the top right corner. For an anonymous user, the menu bar would show links inviting the user to log in or create an account. That bar would change to a user avatar and profile menu for signed-in users. Because the page varied based on user login status, it wasn’t possible to cache any of it in CDNs.

These pages are generated by Server-Side Rendering (SSR) of React components. The fix was to take all the React components that depended on the login cookie, and force them to be lazily rendered clientside only. Now the server returns completely generic pages with placeholders for personalised components like the login menu bar. When a page loads in the user’s browser, these placeholders are filled in clientside by making calls to the GraphQL API. The generic pages can be safely cached in CDNs.

Not only does this trick improve cache hit ratios, it helps improve perceived page load time thanks to human psychology. Blank screens and even spinner animations make us impatient, but once the first content appears, it distracts us for several hundred milliseconds. If people click a Vocal post link from social media and the main content appears immediately from a CDN, very few will ever notice (or care) that some components aren’t fully interactive until a few hundred milliseconds later.

By the way, another trick for getting the first content in front of the user faster is to stream render the SSR response as it’s generated, instead of waiting for the whole page to be rendered before sending it. Unfortunately, Next.js doesn’t support that yet.

The idea of splitting responses for improved cachability also applies to GraphQL. The ability to query multiple pieces of data with one request is normally an advantage of GraphQL, but if the different parts of the response have very different cachability, it can be better overall to split them. As a simple example, Vocal’s pagination component needs to know the number of pages plus the content for the current page. Originally the component fetched both in one query, but because the total number of pages is a constant across all pages, I made it a separate query so it can be cached.

Benefits of caching

The obvious benefit of caching is that it reduces the load on Vocal’s backend servers. That’s good, but it’s dangerous to rely on caching for capacity, though, because you still need a backup plan for when you inevitably drop the cache one day.

The improved responsiveness is a better reason for caching.

A couple of other benefits might be less obvious. Traffic spikes tend to be highly localised. If someone with a lot of social media followers shares a link to a page, Vocal will get a big surge of traffic, but mostly to that one page and its assets. That’s why caches are good at absorbing the worst traffic spikes, making the backend traffic patterns relatively smoother and easier for autoscaling to handle.

Another benefit is graceful degradation. Even if the backends are in serious trouble for some reason, the most popular parts of the site can still be served from the CDN cache.

Other performance tweaks

As I always say, the secret to scaling isn’t making things complicated. It’s making things no more complicated than needed, and then thoroughly fixing all the things that prevent scaling. Scaling Vocal involved a lot of little things that won’t fit in this post.

Here’s one tip: for the difficult debugging problems in distributed systems, the hardest part is usually getting the right data to see what’s going on. I can think of plenty of times that I’ve got stuck and tried to just “wing it” by guessing instead of figuring out how to find the right data. Sometimes that works, but not for the hard problems.

A related tip is that you can learn a lot by getting real-time data (even just log files under tail -F) on each

component in a system, displaying it in various windows in one monitor, and just clicking around the site in another.

I’m talking about things like, “Hey, why does toggling this one checkbox generate dozens of DB queries in the

backend?”

Here’s an example of one fix. Some pages were taking more than a couple of seconds to render, but only in the deployment environment, and only with SSR. The monitoring dashboards didn’t show any CPU usage spikes, and the apps weren’t using disk, so it suggested that maybe the app was waiting on network requests, probably to a backend. In a dev environment I could watch how the app worked using the sysstat tools to record CPU/RAM/disk usage, along with Postgres statement logging and the usual app logs. Node.js supports probes for tracing HTTP requests using something like bpftrace, but boring reasons meant they didn’t work in the dev environment, so instead I found the probes in the source code and made a custom Node.js build with request logging. I used tcpdump to record network data. That let me find the problem: for every API request made by Website, a new network connection was being created to Platform. (If that hadn’t worked, I guess I would have added request tracing to the apps.)

Network connections are fast on a local machine, but take non-negligible time on a real network. Setting up an encrypted connection (like in the production environment) takes even longer. If you’re making lots of requests to one server (like an API), it’s important to keep the connection open and reuse it. Browsers do that automatically, but Node.js doesn’t by default because it can’t know if you’re making more requests. That’s why the problem only appeared with SSR. Like many long debugging sessions, the fix was very simple: just configure SSR to keep connections alive. The rendering time of the slower pages dropped dramatically.

If you want to know more about this kind of stuff, I highly recommend reading the High Performance Browser Networking book (free to read online) and following up with guides Brendan Gregg has published.

What about your site?

There’s actually a lot more stuff we could have done to improve Vocal, but we didn’t do it all. That’s a big difference between doing SRE work for a startup and doing it for a big company as a permanent employee. We had tights goals, budget and launch date. But we ended up with an improved site that’s giving users something they want.

Similarly, your site will have its own goals, and is likely quite different from Vocal. However, I hope this post and its links give you at least some useful ideas to make something better for users.